GUIDES

When UX Designers Should Do Research (And When They Shouldn’t)

May 6, 2025

In 2026, the question is no longer whether UX designers can do research but when they should, when they shouldn’t, and what kind of research actually adds value.

In many organizations, UX designers are increasingly expected to “do research.” Sometimes this expectation is justified. Often, it is a symptom of unclear roles, limited resources, or organizational UX immaturity.

In 2026, the question is no longer whether UX designers can do research but when they should, when they shouldn’t, and what kind of research actually adds value.

This article clarifies:

When UX designers doing research is appropriate

When it becomes risky or counterproductive

How to avoid confusing research activity with research rigor

The Root of the Confusion

UX designers and UX researchers share a common goal: reducing uncertainty to improve user outcomes. However, they approach this goal differently.

UX designers focus on solution shaping

UX researchers focus on evidence generation and validation

Problems arise when organizations:

Expect designers to replace researchers

Treat research as a checklist rather than a discipline

Assume “talking to users” equals research

Understanding intent is more important than job titles.

When UX Designers Should Do Research

There are several scenarios where UX designers conducting research is not only acceptable but necessary.

1. Early Discovery in Low-Risk Contexts

When uncertainty is high and scope is still fluid, UX designers are often best positioned to run lightweight discovery.

Examples:

Exploratory user interviews

Problem framing conversations

Assumption validation

At this stage, the goal is not statistical confidence it is directional clarity.

Why this works

Designers are closest to the problem

Speed matters more than rigor

Insights directly influence design decisions

2. Continuous Feedback During Design Iteration

UX designers should absolutely run usability testing on their own work, especially when iterating on flows, components, or interactions.

Common examples:

Prototype usability testing

Concept validation

Interaction feedback

Tools often used here include:

Figma (interactive prototypes)

Maze (lightweight usability tests)

Why this works

Fast feedback loops

Direct accountability

Clear design ownership

Links:

https://www.figma.com

https://maze.co

3. When No UX Researcher Is Available

In many teams especially startups or smaller organizations UX designers are the only UX function.

In these cases, doing no research at all is far riskier than doing imperfect but intentional research.

Appropriate approaches:

Structured interviews

Basic usability tests

Pattern validation

The key is transparency: clearly state limitations and confidence levels.

When UX Designers Should Not Do Research

There are equally important scenarios where UX designers stepping into research creates false confidence or strategic risk.

1. High-Stakes or Regulated Decisions

In domains such as finance, healthcare, energy, or government, research decisions can have legal, ethical, or operational consequences.

Examples:

Regulatory compliance validation

Safety-critical workflows

Policy-driven user journeys

These contexts require:

Methodological rigor

Auditability

Bias mitigation

This is where dedicated researchers and tools like Dovetail are essential.

Link: https://dovetail.com

2. Large-Scale Quantitative or Longitudinal Studies

UX designers should not be expected to run:

Longitudinal studies

Large quantitative surveys

Behavioral analytics interpretation without training

These require:

Statistical literacy

Sampling strategy

Analytical rigor

Misinterpreting this data can lead to confident but incorrect design decisions.

3. When Designers Are Asked to “Prove” a Solution

One of the most dangerous patterns in UX is asking designers to research after a solution has already been chosen.

In these situations, research becomes:

Performative

Biased

Politically motivated

UX designers should resist doing research when:

Outcomes are predetermined

Negative findings are unwelcome

Research is used as validation theater

The Middle Ground: Shared Responsibility, Clear Boundaries

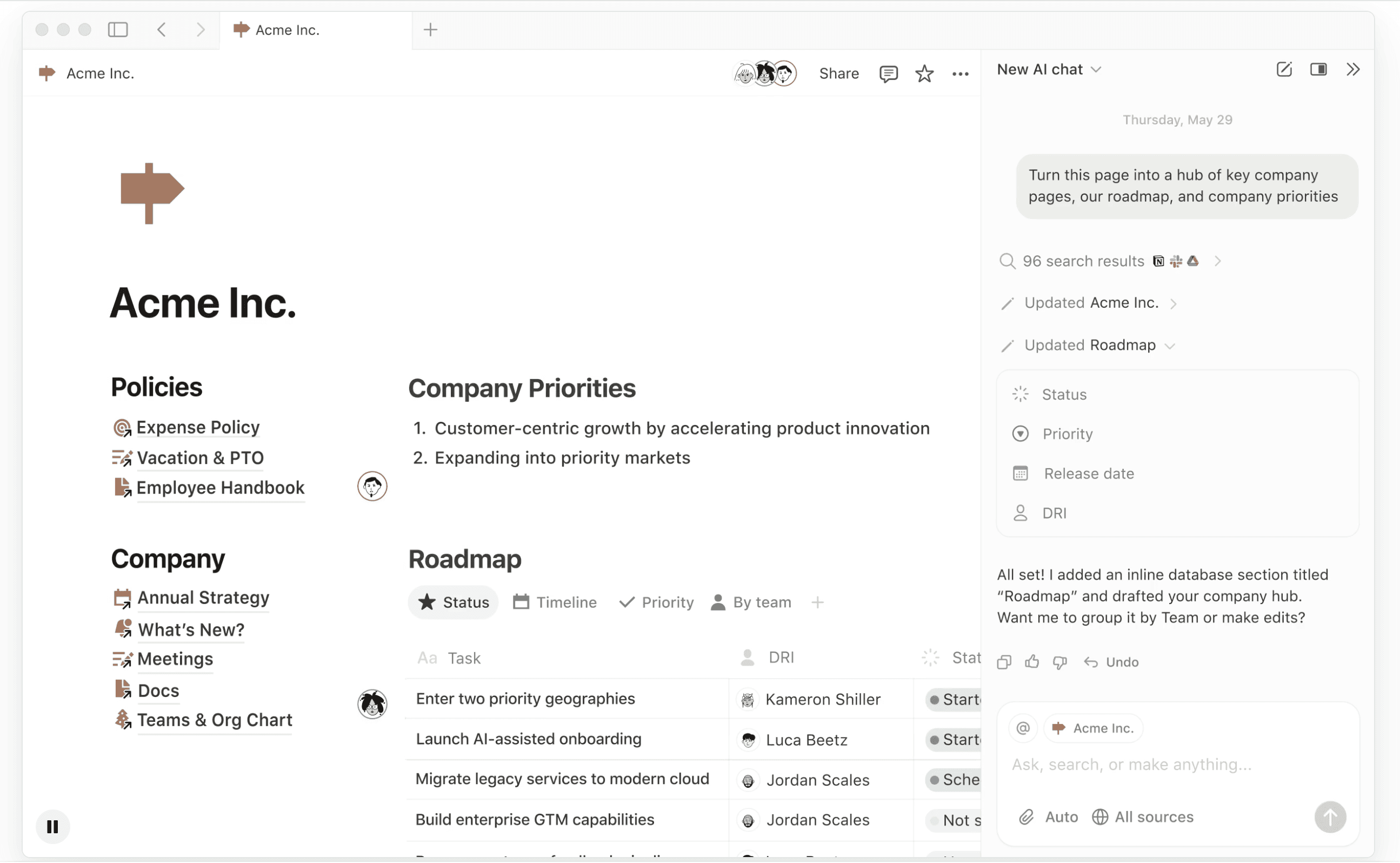

Some tools are shared but used differently.

Miro

Designers: ideation, mapping

Researchers: synthesis, clustering

Notion

Designers: decisions, patterns

Researchers: insights, evidence

Links:

https://miro.com

https://www.notion.so

Clear intent prevents role dilution.

A Simple Decision Framework

Before UX designers do research, ask:

Is this research exploratory or evaluative?

What is the risk of being wrong?

Who will act on the findings?

Do we need speed or rigor?

If speed and learning matter → designers can lead

If rigor and defensibility matter → researchers should lead

Final Thoughts

UX designers doing research is not a problem.

UX designers doing the wrong kind of research for the wrong reasons is.

In mature UX organizations:

Designers explore and iterate

Researchers validate and protect rigor

Tools support intent not role confusion

Understanding when to step in and when to step back is a core senior UX skill.

This article connects directly to upcoming UX Mini-Series episodes and future UX courses focused on real-world UX practice in complex systems.